Two pianists show the difference between playing and performing

On Sunday afternoon, I heard a live performance of a piece I’d just reviewed a few months before: Igor Stravinsky’s four-hand piano version of his seminal “The Rite of Spring,” which caused a veritable riot at its world premiere as a ballet in Paris in 1913. It’s famous for its skewed, off-kilter rhythms and raw drive, and the piano version is made no easier by the fact that the two players have to jockey for room at the keyboard. On Sunday at the Phillips Collection, Dennis Russell Davies, the well-known conductor and pianist, took off his jacket before performing it with his wife, the pianist Maki Namekawa, and observed to the audience that people might want to watch them fighting over who gets to use the pedal.

Both this performance and the one I heard last fall were quite brilliant, but the difference between them was striking. In October at the National Gallery, the duo-piano team Anderson and Roe offered a gleaming, polished reading. On Sunday, Davies and Namekawa presented a dialogue. Anderson and Roe offered sheer power; in Davies and Namekawa’s playing, I heard the specifically pianistic elements of the arrangement emerge, so that it sounded, often, like French piano music. Anderson and Roe showed two voices speaking as one; Davies and Namekawa were distinct individuals, he warmer, powerful and fuller, she insistent and percussive.

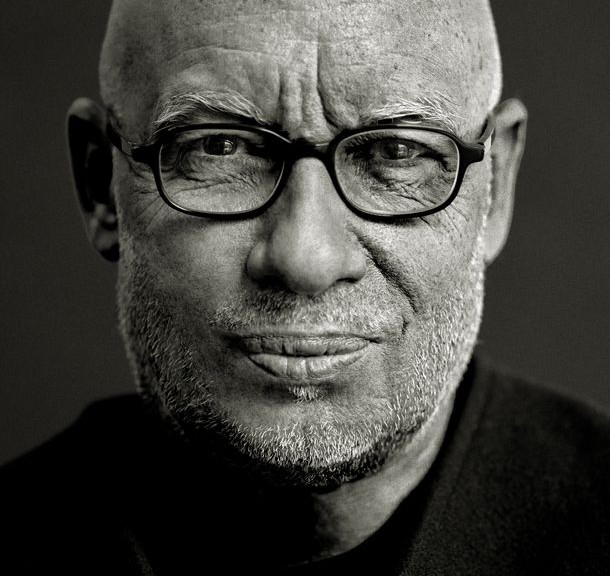

Conductor of the Bruckner Orchestra Linz – Denniss Russell Davies – Foto by Andreas_H_Bitesnich

Pianist Maki Namekawa by Wolfgang Winkler

And Davies and Namekawa, who have both worked extensively in new music and are known as Philip Glass specialists, had no interest in prettifying the music’s raw edges: They unabashedly reveled in harshness and dissonance and jaggedness, presenting it with a kind of matter-of-factness. The contrast even said something to me about the difference between the United States, where we may expect things to be slightly more formal and shiny, and Europe, where Davies and Namekawa have been based for a couple of decades (he has been music director of the Bruckner Orchestra Linz for 15 years) and where their duo piano recitals have been enthusiastically received by music lovers.

The program was beautifully put together, with a web of interconnections between the pieces and making a strong case for unfamiliar music. It opened with Shostakovich’s Concertino for Two Pianos, a work that shows off the composer’s more antic side and offered another Russian voice along with the Stravinsky. After intermission came a piano suite that the Austrian composer Kurt Schwertsik, now in his 80s, created for his own “Macbeth” ballet, filled with touches both sinister and humorous, and containing some of the kinds of repetitions that evoke the idea of minimalism, a la Glass.

The afternoon culminated with a piece as powerful and weighty as the Stravinsky: Glass’s “Four Movements for Two Pianos.” Glass has as distinctive a language as any composer who has ever lived, but those who hear in it no more than repetition would be challenged by the massive intensity, scope and variety and emotional power and sheer motion of these four contrasting miniature works.

Though the program contained only music written in the past 104 years, it was anything but daunting, and the performers, smiling at each other and at the music, emphasized “playing” rather than “performing,” with all the artificial earnestness that the latter entails. It was a performance given by people who cared more about the music than about what you, or I, or anybody thinks of it — a performance at once intimate and uncompromising, a concert given by two working musicians, at work.

Source: Washington Post

By Anne Midgette